Analyzing all of my Messenger conversations to create conversational macros

Why make conversational macros?

For ergonomic reasons, I use free, open-source stenography software to type. This means that I press anywhere from 1 to about 12 keys at once, and get a word. To learn more about it, you can read my post about the mechanics of stenography and my motivation for using it.

In short, machine stenography in the U.S. is a chording, mnemonic keyboarding system. When I press a chord of keys, the software looks it up in a dictionary file and outputs a pre-defined word for me. The dictionary file that comes with the software has many tens of thousands of entries, covering most of English.

Some of these entries are phrases instead of words. For example, I can type “I don’t know” in a single seven-key chord. These are very useful for me, because most of my typing is instant messaging, and these phrases come up a lot.

But this set of phrases is somewhat limited, because the author of the dictionary works in areas like medical transcription rather than instant messaging. Instead of conversationally-useful phrases, there are lots of phrases like “non-small cell lung cancer” which can be produced in one chord.

I’d like to improve the breadth of conversational entries in my dictionary for use in instant messaging. So how do I know which entries to add? The best way is to actually analyze all of my instant messages.

Table of contents:

How do I get all of my Messenger conversations?

Facebook has an option to let you download all of your Facebook data. (Note: it takes a while to prepare the archive, so if you plan to download your data, start the process beforehand.)

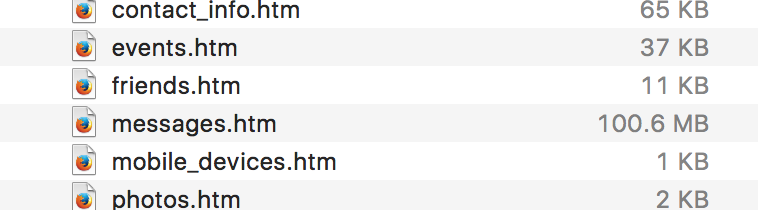

Unfortunately, all of that data is in HTML form. This is not very useful for programmatic analysis. My messages page is 100 MB, and my add-ons choke the life out of Firefox when trying to open it.

All my personal data, held hostage by the tyranny of web standards.

Somebody has already written a script to extract the message data, so I just ran the script and got an 80 MB JSON file containing all of my messages. Below is an excerpt from the beginning of the JSON file:

{

"threads": [

{

"people": [

"David Redacted",

"Waleed Khan"

],

"messages": [

{

"sender": "Waleed Khan",

"date_time": "Monday, March 09, 2015 at 12:16PM ",

"text": "This Wednesday?"

},

{

"sender": "David Redacted",

"date_time": "Monday, March 09, 2015 at 12:16PM ",

"text": "it's going out wednesday"

},

...

Identifying the candidate macros

How do I determine the phrases which I use most? Essentially, I need to look at the top n-grams among my messages. That is, I need to look at the most frequent sequences of words of length 1, 2, 3, …, etc.

Looking at the top sequences of single words would just tell me words like “the” are most common and that I ought to macro them. Of course, I have the word “the” macroed already. Thus, I’m going to start with n = 10 and work my way down until, say, n = 2.

So I need to extract my messages from the JSON and produce the n-grams, and then I need to determine which n-grams appear frequently enough that it’s worth adding a macro for them.

Parsing JSON

I could write a script to parse my messages out of the JSON, but perhaps better

would be to take a opportunity to get practice with jq, which is a

command-line tool to manipulate JSON.

After some finagling, I write the following query. I’ve told jq to produce “raw” output rather than JSON output so that I don’t have to parse JSON again to make use of this data.

$ jq <messages.json --raw-output '.threads[].messages[] | select(.sender == "Waleed Khan") | .text'

This Wednesday?

So I have plenty of time to do my bit, yeah? It's not like we're pushing it out before this project is done

Cool

...

Extracting useful n-grams

Now that I have a text stream of all of the messages I’ve ever said, I need to determine the n-grams for any given n; and furthermore, I only want to output the ones that appear frequently enough.

How do I determine if an n-gram appears frequently enough? Initially, I looked at the n-grams that appeared more often than the average n-gram appeared. But as it turns out, the average n-gram appears between 1 and 2 times for most values of n, so this qualification includes too many n-grams. Arbitrarily, I decided that an n-gram has to appear at least 5 times for it to be worth looking at.

I wrote a short script to find the n-grams:

import collections

import sys

n = int(sys.argv[1])

ngrams = collections.Counter()

for line in sys.stdin:

words = line.split()

line_ngrams = zip(*[tuple(words[i:]) for i in range(n)])

for ngram in line_ngrams:

ngrams[ngram] += 1

average = sum(ngrams.values()) / len(ngrams)

print("Average: {}\n".format(average))

most_frequent_ngrams = sorted(ngrams.items(), key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True)

for ngram, count in most_frequent_ngrams:

if count >= 5:

print("{}: {}".format(count, " ".join(ngram)))

Results

I’ve assembled a selection of the most interesting n-grams that I found. There weren’t useful n-grams beyond about n = 6.

3-grams

Here are the top few results for n = 3. I’ve also annotated which of these were already in my dictionary.

Note that the entries with “<3” and “tsk” were part of very large copy-pasted messages. (That is, there was one very large message with many “<3”s or “tsks” that skewed the counts.) They also appear as top 10-grams, but they’re not really representative of my messages.

Average: 1.3638674842177816

623: <3 <3 <3

618: I don't think (already in dictionary)

594: I have to

568: I don't know (already in dictionary)

437: I love you

434: you want to

385: tsk tsk tsk

313: you have to

289: I'm going to

282: I'm not sure

265: I don't have (already in dictionary)

254: Do you want (already in dictionary)

245: I want to

238: a lot of

218: don't want to

216: I don't want (already in dictionary)

210: to go to

205: I thought you

187: Do you have (already in dictionary)

185: I have a

182: I think I

181: Love you too

181: be able to

178: you have a

176: want me to

176: go to bed

164: don't know what

163: was going to

160: I'm pretty sure

Some of these already appear in the dictionary in a lesser form. For example, “I have”, “have to”, “love you”, “you want”, and “I want”. By being 2-grams, they can be a little bit more flexible than if they were part of a 3-gram. Then I can also say that “I want food” in addition to “I want to get food”.

I had long suspected that “to go to” and variations were part of my most frequently used phrases. It turns out that “going to” already has entries in the dictionary, but I never thought to look for them.

Apparently, I’m usually “not sure” or “pretty sure” about things. This is probably to give myself an out for the cases when I’m wrong about things. Maybe I should reflect on that aspect of my personality.

4-grams

Here are some of my top 4-grams. These are quite insightful, as none of these phrases are in my dictionary, but some evidently ought to be.

Average: 1.0939080011918132

447: <3 <3 <3 <3

382: tsk tsk tsk tsk

144: I was going to

142: I don't want to

138: I don't know what

130: you want me to

124: Do you want to

91: I don't know if

86: I have to go

82: I don't think I

79: I don't know how

75: I thought you were

72: Are you going to

71: Do you want me

70: I don't think so

69: do you want to

63: to go to bed

63: if you want to

62: Did you know that

58: so that I can

55: I have to get

54: I thought it was

52: I don't get it

52: I don't think it's

51: I have no idea

51: are you going to

50: have to go to

49: I'm gonna go to

48: don't know how to

48: I don't have a

Some of my favorites are “I was going to”, “are you going to”, “so that I can”, and “I have no idea”.

6-grams

Here are some of my top 6-grams, none of which were already in my dictionary. There are a couple of anomalies with missed calls on Messenger, because I have never wanted to use Messenger to make a call and every instance of that was an accident.

Average: 1.0098786652250653

413: <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3

377: tsk tsk tsk tsk tsk tsk

20: nom nom nom nom nom nom

15: I have to go to bed

13: Anna missed a call from Waleed.

13: So what you're saying is that

12: don't know what you're talking about

12: I want to go to bed

12: I'm going to go to bed

11: I don't know what to do

10: Talk to you in a bit

10: missed a call from Waleed Khan.

10: I don't know what you're talking

9: What am I supposed to do

9: I don't think you know what

9: Do you want me to come

9: I thought you were going to

9: Why would you want to do

9: I was going to go to

8: would you want to do that

7: I thought you were talking about

7: I don't know how to get

7: What do you want me to

7: I was gonna go to bed

7: me know when you get here

7: Do you want to go to

7: I just don't want you to

7: I don't know if I can

One thing that you can see from this data is that I really like going to bed.

Some phrases from here which might be useful to add to my dictionary are “I don’t know what you’re talking about”, “so what you’re saying is”, and “let me know when you get here”.

Phrases like “I don’t know if I can” and “Do you want to go to” can be formed by two 3-grams (once I update my dictionary with the 3-gram results) so it might not be worth adding those phrases directly.

Related posts

The following are hand-curated posts which you might find interesting.

| Date | Title | |

|---|---|---|

| 19 Sep 2016 | Is having a '.name' email address a good idea? | |

| 13 Oct 2016 | (this post) | Analyzing all of my Messenger conversations to create conversational macros |

| 29 Apr 2020 | I used to run my own mail server | |

| 04 Oct 2021 | Automatically detecting and replying to recruiter spam | |

| 09 Nov 2022 | Update #1: Automatically detecting and replying to recruiter spam |

Want to see more of my posts? Follow me on Twitter or subscribe via RSS.