Language-learning anecdotes

| Intended audience | Those with a passing interest in linguistics. |

| Occasion | April Cools' 2025 — a little late! |

| Origin | Personal experience. |

| Mood | Amused. |

These are some anecdotes from my various experiences learning languages (including Urdu, Polish, Latin, and American Sign Language). The order of entries is mostly arbitrary. Hopefully you find some of them entertaining!

Miscellany

We all scream for ice cream?

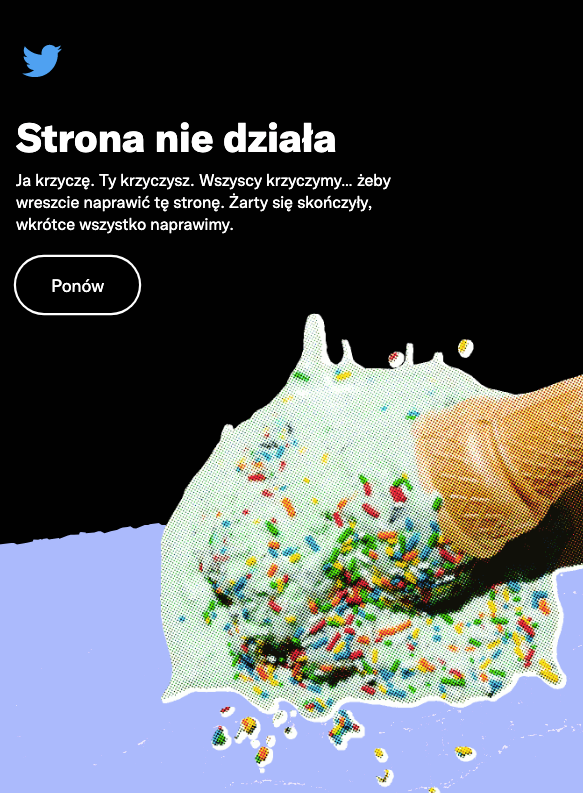

Here’s an error screen from Twitter (from many years ago), localized to Polish:

On this error page, the text along with the ice cream cone in the background refer to the rhyme “I Scream, You Scream, We All Scream for Ice Cream”.

The text roughly translates to:

The page isn’t working

I yell. You yell. We all yell… to finally fix this page. […]

Given that the ice cream rhyme relies on wordplay, it seems very likely that this would be unintelligible to Polish speakers.

Regrettably: Even in English, it relies on the reader making a semantic connection with the background image, which is its own accessibility issue.

On hedgehogs

Here’s someone else’s recollection of a story, which I thought was funny:

I was telling my German colleague about how my parents, who were living in Spain, kept having problems with eagles killing their chickens.

Me: yeah, these eagles come down out of the mountains, they steal the chickens right out of the pen!

Frank: an eagle!? AN EAGLE DOES THIS!?

Me: yes, they have eagles over there, mad isn’t it?

Frank: AN EAGLE IS STEALING THE CHICKENS?

Me: errr, yeah, they’re predators you know?

Frank: THEY ARE PREDATORS?

Me: yeah, and they fly down and kill the chickens and fly off with them

Frank: THEY FLY… wait, hang on… Oh…. I see… Err… In German, Igel is… Errr…

(long, long pause)…

AH! IN GERMAN, EIN IGEL IS A HEDGEHOG!

I had assumed that the German word Igel (“hedgehog”) might be a cognate of Polish igła (“needle”), although I didn’t find a direct etymological connection.

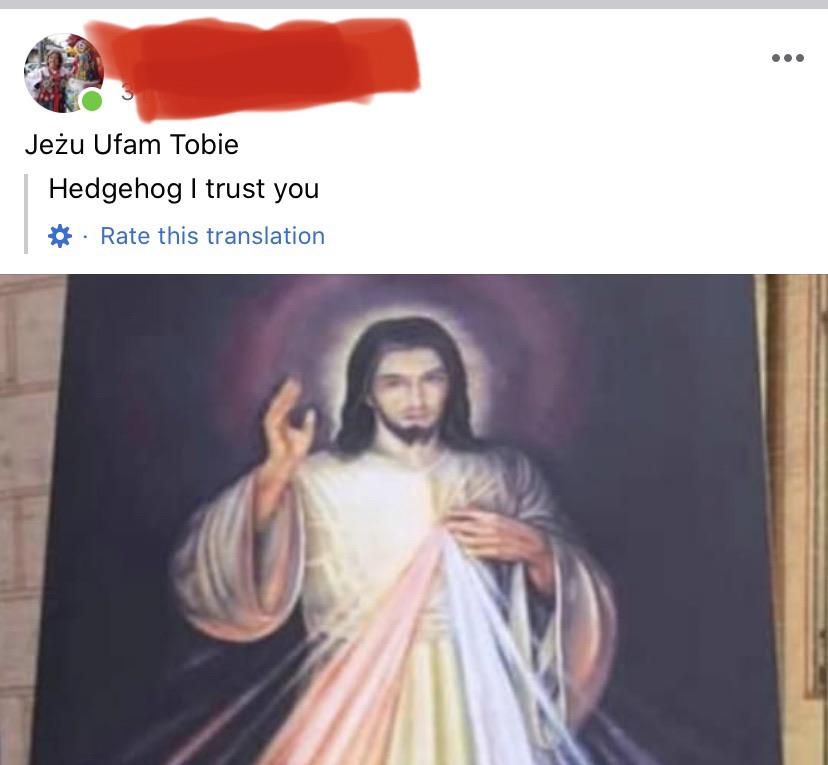

Here’s a humorous misspelling in Polish:

A Facebook post that says “Jeżu Ufam Tobie” with an attached portrait of Jesus. The Facebook auto-translation reads “Hedgehog I trust you”.

This misspells Jezu (singular vocative form of Jezus “Jesus”) as jeżu (singular vocative form of jeż, “hedgehog”). Naturally: I’ve adopted “jeżu” as my expletive of choice in Polish.

The Polish word for “porcupine” is jeżozwierz:

whose components might translate to “hedgehogobeast”, which I thought was fun.

Social deduction

My family took my wife and I to buy her a lehenga for our wedding celebration. My father advised me that they expected to haggle, as is tradition:

- On the buyer’s side: We wanted to avoid giving away information and losing negotiating leverage, so I communicated with my wife in Polish, which only my wife and I spoke.

- On the seller’s side: They spoke with my parents in Urdu, which my wife doesn’t speak.

- We would switch to English when we all needed to converse.

For a few minutes at a time, I would undergo what I found to be perhaps the most mentally-taxing activity of my life: conducting a many-way negotiation with hidden information across three languages.

To elaborate: I had to translate between Urdu (weak) and Polish (non-native), going through my native English as an intermediary, in close to real-time.

Since my grasp of Urdu is weak, I missed several contextual and cultural clues, and had to explain

- not only the facts I understood,

- but the inferences I was making

- and the confidence I had in those inferences.

- But in Polish.

Furthermore: I had to play a careful kind of social deduction game, in which:

- I had to keep in mind which information each of the parties had:

- my wife and her judgments;

- myself and my own judgments;

- my and my wife’s joint public statements;

- my family’s public statements;

- and the seller’s public statements;

- what I know my family knows and believes privately, which I have to be careful not to undermine;

- how my family would interpret my and my wife’s joint statements, based on what they know we know.

- I had to be sure to convey public information between all relevant parties, while avoiding leaking private information.

For example: Suppose my family were to claim “we’re visiting a few more shops after this”, when in fact we had nothing else on the agenda for the day:

- Then I would have to be careful to secretly get my wife to corroborate, in order to avoid undermining our negotiating position,

- or I’d have to consider what I was signaling if I chose to contradict my family.

Forgetting my native language

I largely dropped Urdu at home:

- My parents would speak in Urdu and I would reply in English.

- This is a common situation in immigrant households. I don’t know if it has a name.

- Since they were already fluent in English, over time, they largely switched to English at home.

- Having failed to acquire Urdu well, I also got frustrated easily, or failed to understand some speech entirely,

- which no doubt led to a feedback loop of encouraging English to be spoken at home.

Oops: In university, I took an introductory linguistics course. We all filled out a brief survey, including information about which languages we spoke. By that point, I forgot to fill in ‘Urdu’ 🙃.

Sentence formation

Hacking the Latin word ordering

In university, I took a Latin course:

- English uses subject-verb-object (SVO) word order,

- while Latin is highly-inflected. The word order is largely free-form, but conventionally subject-object-verb (SOV).

I encountered a great deal of mental friction as I tried to order the sentence components in the conventional SOV manner.

Then I realized — my other native language, Urdu, also has SOV word order. And suddenly it became trivial!

Interestingly: It was as if I mentally rearranged merely the sentence’s concepts in SOV order by passing them through some Urdu circuit in my brain, while relying on my English ability for everything else relating to sentence formation.

To elaborate: I didn’t have enough familiarity or vocabulary to actually translate anything into Urdu as an intermediate step.

- So this only leveraged my instinctive syntactic and parsing ability, and nothing semantic.

- Just as before: I didn’t get to leverage instinctive noun agreement.

- In any event: English vocabulary is much more similar to Latin (via French) than Urdu vocabulary is, so the literal translation of concepts is easier directly from English to Latin.

Concretely: I found SOV a little difficult when thinking in SVO:

- In SVO, once you reach the verb, you know you that you’re done parsing the subject’s noun phrase, and can “unwind” it,

- whereas in SOV, you might have to build up two complicated noun phrases — and distinguish their boundary — and keep them in mind simultaneously.

-

I felt that I primarily relied on the syntactic ability to juggle both noun phrases at once.

Making my English worse with Latin

Latin uses participles more often than English, which is described well here. This bled into my “natural” or “default” English, and has led to me using sometimes-unconventional participial phrasing:

- For example: “Someone having learned Latin might use participles more often” rather than “Someone who’s learned Latin might use participles more often”.

- For example: “With me having learned Latin, I use participles more often” rather than “Given that I’ve learned Latin, I use participles more often”.

Making my English worse with Polish

Learning Polish has made my English more non-standard:

- I sometimes build up adjectival or adverbial clauses that are uncomfortable to parse, rather than spreading them throughout a sentence more naturally.

- For example: “I learned Polish, which caused me to more-unusually order adverbs” rather than “I learned Polish, which caused me to order adverbs more unusually”.

- I sometimes use verbal nouns when subordinate clauses would be more conventional.

- For example: “My having learned Polish caused me to use verbal nouns unconventionally rather than “I learned Polish, which caused me to use verbal nouns unconventionally”.

Preferring a completely-foreign word order

Similarly to Latin, Polish is a language with conventionally SVO word order, but with enough inflection to support technically free-form word order.

After achieving basic fluency in Polish, I noticed that my preferred word order was most often verb-subject-object (VSO)!

This was unexpected: None of my languages conventionally use VSO, so it’s interesting that I might prefer it, despite having no (grammatical) way to express it in my available languages.

Possibly: It might reflect a desire to express topic-comment word order,

- rather than specifically VSO, supposing that I’m most often commenting on actions.

- Possibly: My inclination to structure discourse as a top-level comment followed by hierarchical detail might be the same thing.

- Likewise for my inclination to

- extract and format mood/uncertainty/provenance signifiers, like “Possibly:”,

- separately from the semantic or factual content of the sentence.

- It’s information that I want to include, but without muddling the syntax.

- You may disagree that the result is any clearer 🙃.

Note: In Polish, the verb embeds the grammatical number of the subject, which is a fairly common language feature.

- Therefore: Saying the verb first also reduces the latency of information transfer, in some sense.

- Despite this: I would often still be inclined to include the subject explicitly after the verb.

- Even if it’s a largely-redundant subject pronoun, due to the grammatical number already being embedded in the verb.

- For example: I might say “zrobili oni to” rather than just “zrobili to”.

- “zrobili”: “to do” third-person plural past-tense perfective

- “oni”: “they” third-person plural

- “to”: “it”/”this” third-person singular

-

For a native speaker, I expect that it would be interpreted as emphasizing the subject much more strongly than I intended it?

Failing to communicate privately in American sign language

My wife and I learned a few signs of American sign language (ASL).

Originally: I thought that ASL could be useful when traveling:

- Particularly: In loud or distant contexts, such as restaurants, parties, public transit, sightseeing, and so forth.

- For example: It can be convenient to communicate from across a museum hall my intention to go to the bathroom, so that my partner isn’t confused about where I’m going, and knows that I’ll return shortly.

- For example: It’s great for excitedly and efficiently summoning the other partner to come see a cute local cat or dog which might soon leave sight.

We’re often able to speak in Polish to communicate privately, but that’s not an option if we happen to be around other Polish speakers, or if we simply can’t hear each other. So I thought it might be convenient to sometimes use ASL for private communication.

But it turns out: Communicating a desire to leave the current venue by gesturing at ourselves and then pointing at the exit with both index fingers is not a terribly polite way to coordinate our departure from a friend’s event.

Pronunciation

Phonological production in Polish, but not distinction

Polish has two phonologically-distinct ‘ch’ sounds, as opposed to English’s one:

- The two sounds are usually written ‘cz’ and ‘ć’

- corresponding to IPA /t͡ʂ/ and /t͡ɕ/

- although with some additional orthographic rules, such as ‘ć’ sometimes being written ‘ci’.

- Polish also has two ‘sh’ and two ‘zh’ sounds with the same phonological relationships.

I can produce these sounds reasonably well, but I nonetheless can’t reliably distinguish them:

- When I hear a new word that uses one of the sounds, I usually ask the speaker “is it (version with cz) or (version with ć)?”.

- It doesn’t help that the word for “or” in these questions is ‘czy’, involving another instance of the ‘ch’ sound.

- Then they repeat back one of the forms to me, after which I realize I can’t distinguish it anyways.

- Then I give up and either ask them to spell it, or I look up the word later.

This is unsurprising from a linguistic perspective, but amusing to me nonetheless.

Subvocalizing written Chinese

I was briefly learning written Chinese, but not spoken Chinese.

- (I have fun learning and writing the characters, but I don’t have anyone to speak Chinese with.)

- Consequently: I didn’t have names or vocalizations for any of the characters, beyond some of the radicals.

So what did I do when I happened to subvocalize characters while practicing? I would just pronounce the Polish word for the same concept!

For example: “水” would become “woda” rather than “water” or “shuǐ”.

Apparently: I just compartmentalize my vocabulary into “native” and “foreign”, without much nuance beyond that!

Adjusting my English accent

At work, we once had several visitors from my team’s other offices. In one instance, at lunch, we had a majority of people with British or Australian accents rather than American accents (perhaps 3–4 vs 2).

Somewhat embarassingly: Once the conversation seemed primarily British-/Australian- rather than American-accented, I found myself adopting their accents without voluntarily deciding to do so 😬:

- I had said e.g. “queue” instead of “line”.

- I switched to using rising inflection for my questions rather than falling inflection,

- Nobody else at the table commented, so I don’t know if they noticed, but perhaps it came off as pretentious 🙃.

- I don’t recall this ever happening again for my English.

- At least: Not to such an alarming degree, anyways. I do naturally adopt various other speech patterns, code-switch, etc.

- My team lead at the time (whom I saw most days, as was normal in the Before Times) had a British accent:

- So I had probably ingested it passively over time,

- but I’d never voluntarily or involuntarily mimicked it.

Making others’ Polish accents worse

In English, out of enthusiasm, I’ll often lengthen certain vowel sounds, such as “hi-iii” or “tha-ank you-uu”. Without consciously considering it, I carried over the same behavior to Polish, such as “cze-eść” (cześć, “hello”) or “dzięku-uję-ę” (dziękuję, “thank you”).

My wife and brother-in-law have informed me that this is simply not done in Polish, and, in fact, I have started to poison their own speech patterns 😈.

Failing to improve my Polish accent

I learned Polish at a basic level to communicate with my wife’s family. When speaking to them in Polish, particularly her parents, I don’t tend to pick up their accent or pronunciation.

But, when abroad, dining with my wife’s cousins (and their respective dinner partners), I noticed involuntary effort on my part to match their pronunciations. I don’t know what the difference is.

To conjecture: It’s hard to decide whether it’s primarily due to low engagement (and compensating to make up for it) or high engagement (encouraging me to absorb more). Maybe a linguist would know. Some ideas:

- I think my wife’s parents speak more quickly than average. It tends to be harder for me to follow/understand them.

- Maybe: I can’t “hear” the pronunciation as well when the speech is quicker.

- Maybe: I need to expend more mental effort on semantic comprehension, and have less available mental throughput to spend on comprehending and analyzing our styles, and matching mine to theirs.

- Maybe: I talk about more engaging or interesting topics (to me) with people my own age, somehow motivating me to analyze the pronunciation more.

- Maybe: I’m naturally more engaged with unfamiliar pronunciations and accents, and perhaps don’t “hear” familiar pronunciation/accents anymore.

- Maybe: Some specific accents are easier for me to analyze and match.

- Maybe: The accents of Polish speakers in America have integrated the ambient phonology somewhat, thus causing the accents to stand out less to me, to the point where I don’t feel the inclination to match them.

Grammar

Urdu gender confusion

I grew up in Michigan, with my immediate family having settled there. I was raised with primarily English and secondarily Urdu as native languages.

Additional background: I always spoke Urdu haltingly:

- Both of my parents spoke English fluently, but would usually speak Urdu at home.

- My vocabulary was very limited,

- but I largely understood the syntax in that intuitive first-language way.

- Presumably due to having acquired it during the critical period.

- My brain will parse utterances I overhear into syntax trees “in the background”:

- without deliberately choosing to expend mental effort,

- and despite the fact that I don’t understand almost all of the words.

- This is unlike Polish, which I learned as a second language to a basic conversational level.

- Note: While I had a solid grasp on the syntax, I had a poor grasp of the grammar, which involves semantic agreement; see later.

-

I was never literate in Urdu.

My mother would take my sister and I to visit our extended family in Pakistan over summer break:

- Everyone lived in one large home and spoke Urdu.

- During the day:

- The women would stay at home to do the housework and childcare, or leave for errands.

- The children would stay at home. The other children were girls (my sister and cousin).

- The men would commute to their respective workplaces in the morning and return in the evening.

- One of my uncles would actually stay in another city during the workweek, and only come home for the weekends! That seems uncommon in the States.

Consequently: The majority of my language-acquisition time was spent among exclusively women.

In Urdu, verbs are conjugated according the subject’s grammatical gender (but see below). Despite my having masculine pronouns, I primarily observed speakers with feminine pronouns, and hence I learned all of the feminine forms instead.

That is: I only knew how to refer to myself as a woman!

To elaborate: Here’s some more details on the grammar:

- For example: The first-person singular pronoun is always “mai”. But to say “I do”, one would say either “mai karta hun” (masculine) or “mai karti hun” (feminine). I only learned the latter form.

- Furthermore: Urdu has split ergativity, so, under specific conditions, the verb agrees with the object instead of the subject.

- This would have been completely inscrutable to me as a child.

Truly: The poverty of the stimulus lays in shambles.

Polish gender confusion

Amusingly: Like Urdu, Polish also conjugates some verbs according to the speaker’s gender. Also like Urdu, I mis-trained the gender of some verb forms based on my available practice partners!

- I learned/trained primarily with my now-wife, as well as her Polish friends who lived in the same building as us.

- Consequently: I overtrained the feminine second-person verb forms, and had to untrain them to speak correctly when encountering a non-feminine audience.

- Unlike Urdu, I knew the correct grammar. I had just built incorrect habits and heuristics.

Urdu grammar confusion

Despite having acquired some facets of Urdu as a first language, I failed to acquire several critical features:

- For example: I don’t have any instinctual noun classification/agreement beyond what exists in English,

- which is unfortunate, because it might have been nice to automatically have instinctive noun agreement in other languages, such as Spanish.

For whatever reason: My younger sister learned Urdu more fluently than I did.

Related posts

The following are hand-curated posts which you might find interesting.

| Date | Title | |

|---|---|---|

| 24 Aug 2016 | Steno Journal: Weeks 1-12 | |

| 06 Sep 2016 | Stenography adventures with Plover and the Ergodox EZ, part 1 | |

| 06 Sep 2016 | Stenography adventures with Plover and the Ergodox EZ, part 2 | |

| 21 May 2018 | My steno system | |

| 05 Apr 2025 | (this post) | Language-learning anecdotes |

Want to see more of my posts? Follow me on Twitter or subscribe via RSS.